When Ghislain’s father died in Congo Brazzaville last year, the threat of either prison or death meant the 35 year old father of one could not go home to bury him. Instead, he wept alone in his room in the house he takes care of in Cape Town.

After civil war broke out in Congo Brazzaville, Ghislain fled to neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo. When he returned home a year later he was accused of being a rebel, and arrested.

After being released and detained three times, he escaped from prison with help from a sympathetic rebel commander, and fled to South Africa in 2011.

For the five years since his arrival, the 35-year-old asylum seeker has been at the mercy of the South African government, waiting in limbo for his appeal to be awarded refugee status to be heard. His initial application for asylum was rejected.

His chances of being granted asylum in South Africa are uncertain, even slim. For now, he waits, and like many others is forced to sacrifice up to two days at a time every three months to renew his asylum permit at the Temporary Refugee Facility in Cape Town.

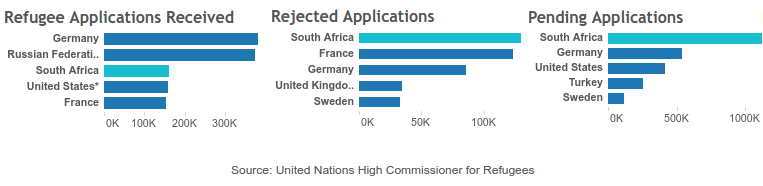

South Africa rejects more refugee applications than any other country in the world, according to an analysis of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) data conducted by Code for South Africa’s Data Journalism Academy.

The data shows that South Africa turned down 81% of the refugee applications it received during 2014 and the first half of 2015, compared to the international average of 21% for the same period.

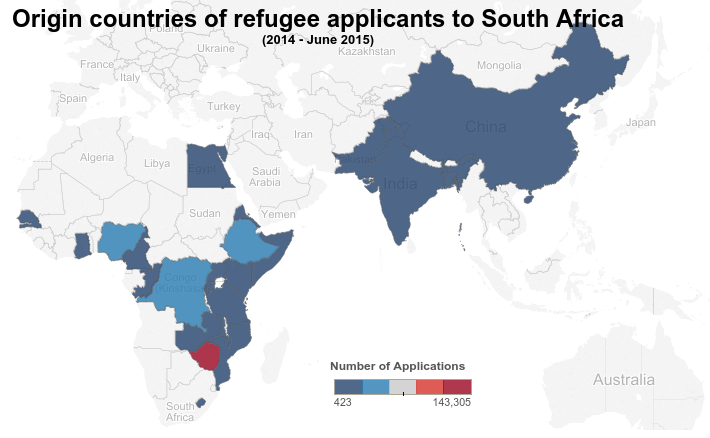

Click on the images for an interactive version

That means that South Africa received the third highest number of applications for refugee status in the world. This, during a time when Europe received one of its largest influxes of refugees from Africa and the Middle East, fleeing war in Syria and the aftermath of the Libyan war, and the expansion of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) across the Middle East.

The UNHCR data also revealed that, with nearly 800 000 cases, South Africa had over a third of the world’s pending refugee applications.

The UNHCR data showed a trend: the majority of asylum applications received by South Africa come from African and Asian countries, including Bangladesh and India. This preference, combined with a massive backlog in the processing of applications by the Department of Home Affairs, created a humanitarian crisis that saw thousands of people struggle in situations much like Ghislain’s.

Roni Amit of the African Centre for Migration and Society at Wits University, whose research in 2012 showed that only around half of all refugee applicants were economic migrants, suggested that the government was intentionally conflating immigrants with refugees to keep people out.

Said Amit: “The rejection rate is so high because they use it as a migration management method to keep people out of the country – it is in their interest. They see all refugees as economic migrants.”

“Part of the problem is the demand on the system, and Home Affairs didn’t increase its capacity because it wanted to decrease demand.”

But spokesperson for the Department of Home Affairs, Mayihlome Tshwete said this was not aimed at preventing people from seeking asylum in SA. Instead, he said the department believed that fraudulent claims by economic migrants who made “deliberate attempts to abuse the system” by applying for refugee status when it wasn’t warranted, were the cause of the backlog.

Since 2012, the government has closed refugee application centres in Port Elizabeth, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

The department of home affairs rejected 96% of refugee applications in 2015, according to a report on asylum statistics for that year, presented to Parliament on the 8th of March.

The report said that by the end of the first quarter of 2015, 2406 people were granted asylum. For the rest of the year, only a further 93 applications received a positive ruling.

According to the department’s report: “Following the SCRA process of monitoring the quality of RSDO’s adjudication and decisions, RSD figures shifted drastically from approvals and unfounded towards manifestly unfounded decisions; thus, confirming the department’s assertion that most new asylum applications are not genuine asylum seekers but rather persons seeking employment or other socio-economic opportunities in the country.”

But this monitoring practice has since been disbanded due to capacity constraints, according to the report.

At the heart of the problem was the failure to have properly qualified, trained RDSO’s, according to attorney William Kerfoot, from the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) in Cape Town. The LRC assists with up to 6000 asylum seekers’ appeal cases annually.

“The latest fashion is under-educated, incompetent refugee status determination officers (who) view each application as fraudulent and therefore as manifestly unfounded,” Kerfoot said. “If they don’t say it’s fraudulent, they say it’s unfounded.”

“In many instances they have the power of life and death in their hands and they get it wrong most of the time. They commit procedural and substantive errors on a daily basis.”

Tshwete admitted that there was a problem with capacity within the department, but said that there were deliberate attempts to abuse weaknesses in the process when it came to capacity.

“People are seeing that the easiest way into SA is as an asylum seeker,” Tshwete said. “We have a majority of people who know that they can apply and also know that they can appeal and still stay for up to five years. Even with manifestly unfounded judgments people still know they can appeal.

“Many people, like those from Zimbabwe, come from countries that aren’t in civil war. We get the impression that most asylum seekers from these countries are economic migrants.

“Our system is liberal, and by its nature it casts a wide net and makes it harder to distinguish between genuine (applications) and not. We need to remove economic migrants from the asylum process so that we can assess them properly.”

Tshwete said the department had plans for amendments to increase capacity which it would be pushing for in the next two years, but would not give further details.

For now, Ghislain joins the ranks of the 150 000 asylum seekers that have come to South Africa, and the thousands among them who exist in a years-long state of uncertainty; in the long queues at the refugee application centres, caught up in a constant battle with bureaucracy, prevented from starting over, but unable to go back.

The article was originally published by TimesLive on March 22, 2016

Resources

DFID – UK Department for International Development [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – Refugee statistics 2014

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – Refugee statistics mid-year trends 2015

Tableau

Farren Collins and Lotte Manicom (own work)