Rest easy. If you are on the Banting diet, you cannot be held responsible for the increase in cauliflower prices — at the wholesale level anyway — over the past few months.

Demand for cauliflower, especially in suburban supermarkets, has increased.

The Banting diet was made popular by sports health scientist Tim Noakes in his book, The Real Meal Revolution. Noakes has attracted admiration and criticism for his support of a low-carbohydrate and high-fat diet, which is not consistent with mainstream scientific views.

To compensate for the absence of carbohydrate-rich foods such as bread and rice, Noakes advises people to eat cauliflower.

The growing popularity of the Banting diet has caused sharp growth in demand for cauliflower-based dishes such as cauli-rice and cauliflower pizza bases.

It has also fueled speculation that the diet is behind a rise in cauliflower prices.

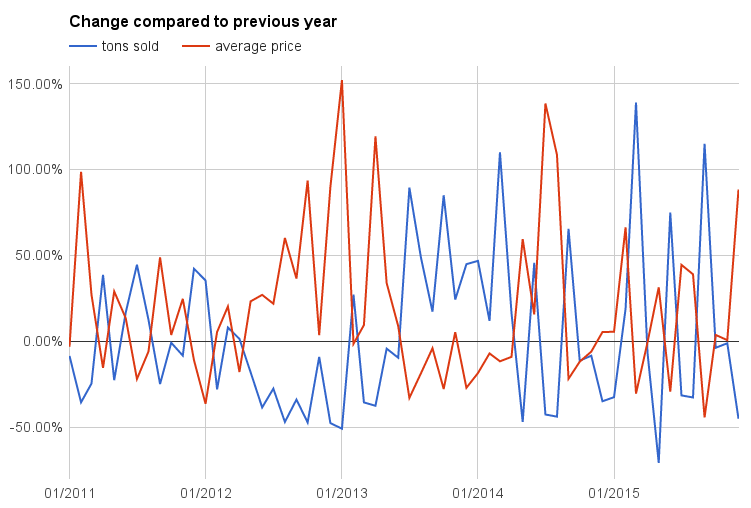

But data gathered by the Code for South Africa Data Journalism Academy on vegetable production and pricing in Cape Town from January 2011 to December 2015 found little basis for this belief. Instead it showed a strong correlation between supply and pricing, with available supply seemingly driving price.

For example, cauliflower sales rose by 74% year on year to 220 tons in June 2015, which was matched by a 29.45% drop in the average selling price to R4,489/t. The inverse was true for June 2015, when sales dropped 32.6% to 164t, but the average selling price shot up by 44.45%.

The correlation is so strong, it looks as though it comes straight out of an economics textbook.

Agri SA senior economist Thabi Nkosi is not surprised by the efficiency in the cauliflower market. As fresh produce expires quickly, it suits both buyers and sellers to reach a price with little delay.

“When it comes to vegetables there is a short time frame between production and consumption,” she points out.

The data also shows that the volume of cauliflower available for sale had trended upwards since Noakes started punting the diet in early 2014. Average prices per ton fell over this period.

But some consumers point to a recent spike in prices. This may be explained by a seasonal trend: cauliflower production spiked in October, resulting in a fall in prices.

After that, sales fell 45% to 142t when measured y/y in December, and prices surged 88% to an average of R5,112/t for the month.

The data, however, does not tell the whole story. Once the cauliflower leaves the gates of the Cape Town Market, prices will vary from retailer to retailer.

Nkosi says she “would not say that the Banting diet has anything to do with [prices] .” The rise should be seen against a background of overall food price hikes, a consequence of drought, she says.

The SA Reserve Bank said in January that it expected food price inflation to rise to 11% y/y in the fourth quarter of 2016. This is the highest rise in five years and sharply up from the 5.9% increase recorded in December 2015.

This article was originally published by Financial mail on March 10, 2016

Resources

Xosema (Own work) [GFDL or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Western Cape monthly market reports – vegetables

Price per market per month

Change in sales and price